Editor’ s Note:

Recently, Shanghai Second Intermediate People's Court held a hearing on the case of Bruce Lee Enterprises v. Zhengongfu over a trademark dispute. Many insiders say that it would be difficult for Bruce Lee Enterprises to invalidate Zhengongfu’s trademark under Article 45 of the Chinese Trademark Law, citing the legal battle between former NBA superstar Michael Jordan and Qiaodan Sports as an example. These two disputes over trademarks prompt us to rethink the limitations of Article 45 of the Chinese Trademark Law compared with Article 9 of the EU Trademark Directive (2015/2436), which provides a longer protection period for prior rights holders and forbids malicious registration with no requirement of trademark reputation.

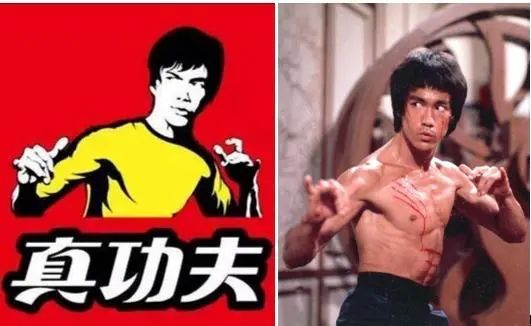

On August 25, Shanghai Second Intermediate People's Court held a hearing on the case of Bruce Lee Enterprises v. Shanghai Zhengongfu Fast Food Management Co., Ltd., Guangzhou Zhengongfu Catering Management Co., Ltd., and Guangzhou Zhengongfu Fast Food Chain Management Co., Ltd. (collectively referred to as Zhengongfu (真功夫) over a trademark dispute.

Earlier on December 5, 2019, the Shanghai Second Intermediate People's Court accepted the case. The plaintiff then asked Zhengongfu to cease using Bruce Lee image (in marketing materials and signage), clarifying in the media for 90 consecutive days that it has no connection with Bruce Lee, and requested the court to order Zhengongfu to pay 210 million yuan in economic losses and 88,000 yuan in reasonable expenses (about $30 million USD). But Zhengongfu, who has used the trademark for 15 years, said, " We do not infringe and will not seek an out-of-court settlement. We have no plans to replace the brand logo. The 210 million Yuan claim has no factual and legal basis."

Zhengongfu was founded in 1990 and is now a leading fast food brand with a number of restaurants in China. It had been called "168 steamed fast food restaurant" before 2014. In 2014, the restaurant changed its name to “Zhengongfu” and filed a trademark application. In 2018, it successfully registered the trademark presenting a martial artist dressed in a yellow top. In 2016, the company upgraded its brand image and logo, using more blurred facial features of the character. The design, however, is deemed by some insiders to be similar to its old version.

However, many insiders say that it would be difficult for Bruce Lee Enterprises to invalidate Zhengongfu’s trademark under Article 45 of the Chinese Trademark Law, which stipulates “that the prior right holder or the interested party may request the Trademark Review and Adjudication Board to declare the registered trademark invalid within five years from the date of trademark registration. For malicious registration, the owner of a well-known trademark is not subject to a five-year time limit.” Considering that the trademark has been used by Zhengongfu for more than 10 years and is now a well-known brand, chances are small for Bruce Lee Enterprises to invalidate Zhengongfu’s trademark, according to a senior lawyer.

Besides, the dispute bears some similarity to the epic legal battle between the former NBA superstar Michael Jordan and Qiaodan Sports Co. Ltd. In 2012, Michael Jordan filed a lawsuit against Qiaodan Sports, alleging that the company has infringed his name rights and requested the cancellation of its multiple trademarks. The two sides were in dispute for more than 9 years until March 2022, when the Supreme People's Court(SPC) refused multiple retrials applied by Michael Jordan where the disputed trademarks were all registered more than 5 years.

SPC’s final decision on the dispute between Micheal Jordan and Qiaodan Sports has drawn wide attention and raised questions about the limitations of Article 45 of the Chinese Trademark Law. Compared with Article 9 of the EU Trademark Directive (2015/2436), which stipulates that “Where, in a Member State, the proprietor of an earlier trademark as referred to in Article 5(2) or Article 5(3)(a) has acquiesced, for a period of five successive years, in the use of a later trademark registered in that Member State while being aware of such use, that proprietor shall no longer be entitled on the basis of the earlier trademark to apply for a declaration that the later trademark is invalid in respect of the goods or services for which the later trademark has been used, unless registration of the later trademark was applied for in bad faith”, there are two major limitations of the Chinese Trademark Law.

Firstly, the EU Trademark Directive provides a longer protection period for prior rights holders, and is more in favor of prior legitimate rights and interests. The five-year period stipulated in the Chinese Trademark Law starts from the date of trademark registration, while the five-year period stipulated in the EU Trademark Directive starts from when the prior right holder has known and acquiesced the use of the trademark. Besides, the EU Trademark Directive requires the trademark right holder to use the trademark for five successive years.

Secondly, the EU Trademark Directive forbids malicious registration with no requirements of the trademark reputation and trademark can be invalid as long as it is obtained by malicious application. In contrast, in accordance with the Chinese Trademark Law, only the owner of a well-known trademark can make an invalid request after five years of its registration, which means that other prior rights holders have lost the right to invalidate a registered trademark after five years and the malicious registrant can legalize its illegal rights.

To conclude, Article 9 of the EU Trademark Directive can provide reference for Article 45 of the Chinese Trademark Law. Malicious applicants, who are motivated to obtain improper benefits and hitchhike when applying for a trademark, should not be able to make trademark valid after a certain period of time. For trademarks registered in bad faith, the prior right holder shall have the right to remedy at any time.